case study

Saffia: AI-platform and app concept

For my capstone project for the MA Design Leadership program, I worked with a partner, Lindsey Weisman, to apply the design thinking process to an issue that was complex, controversial, and highly ambiguous—combating misogyny and advancing feminism.

Project included:

User Research (interview, survey development and data analysis, secondary research)

Synthetic Persona Development using GenAI (ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity)

Concept Testing and Refinement (using both synthetic personas and real human users)

Iterative Design

Prototype (Figma) and user testing (human users only)

Pitch deck

The Problem

Young women entering the workforce are unaware of the gendered headwinds women might face—and many don’t have the tools to address it.

When something they experience doesn’t sit right with them, they are seeking answers to the questions:

Is what I’m experiencing part of a pattern?

Am I actually contributing to this problem and I don’t realize it?

What can I do or say about it?

And am I seeing something that isn’t there?

And it’s not just women. Many men are asking some of the same questions so that they can be better colleagues and leaders in their workplace.

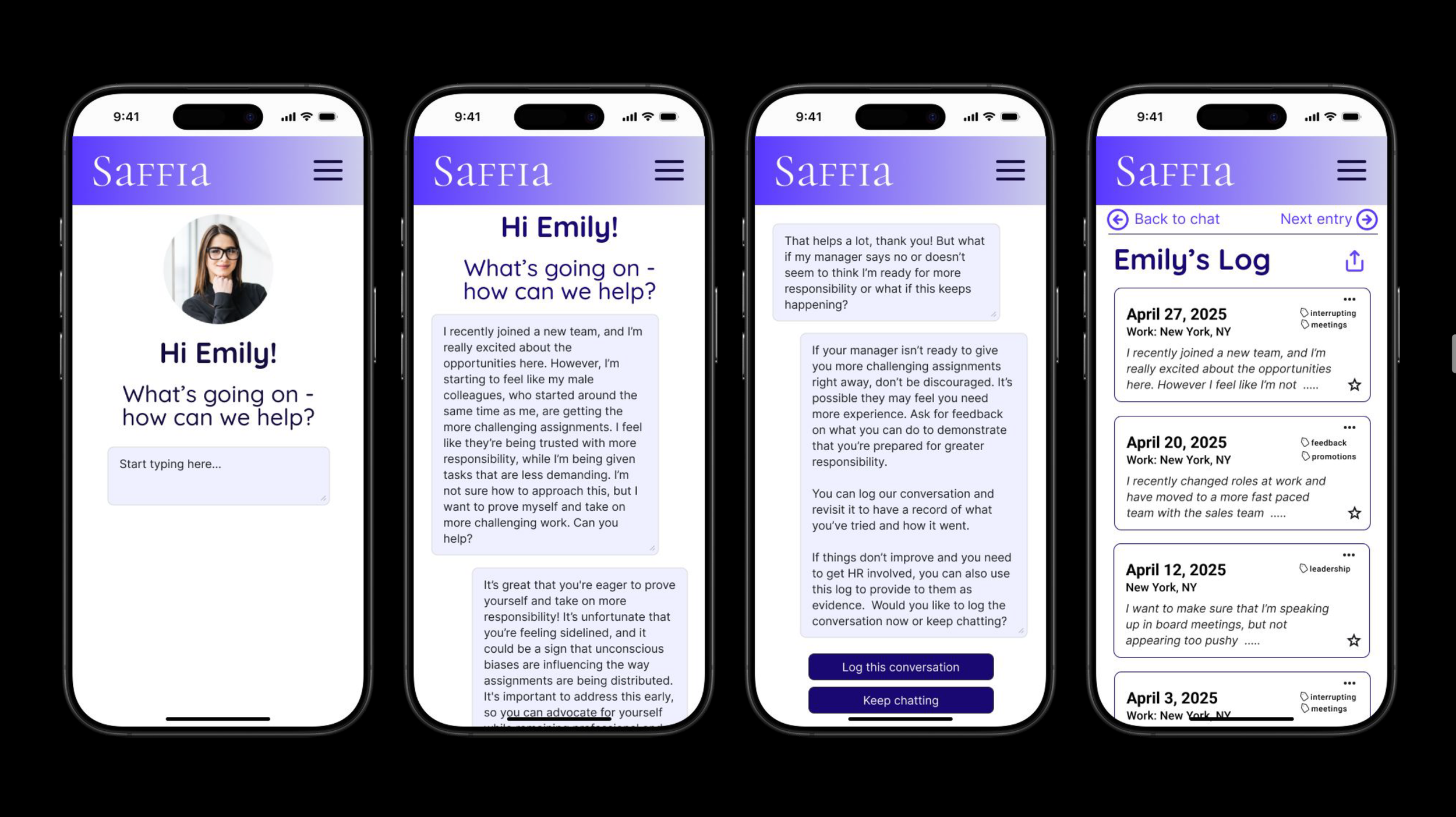

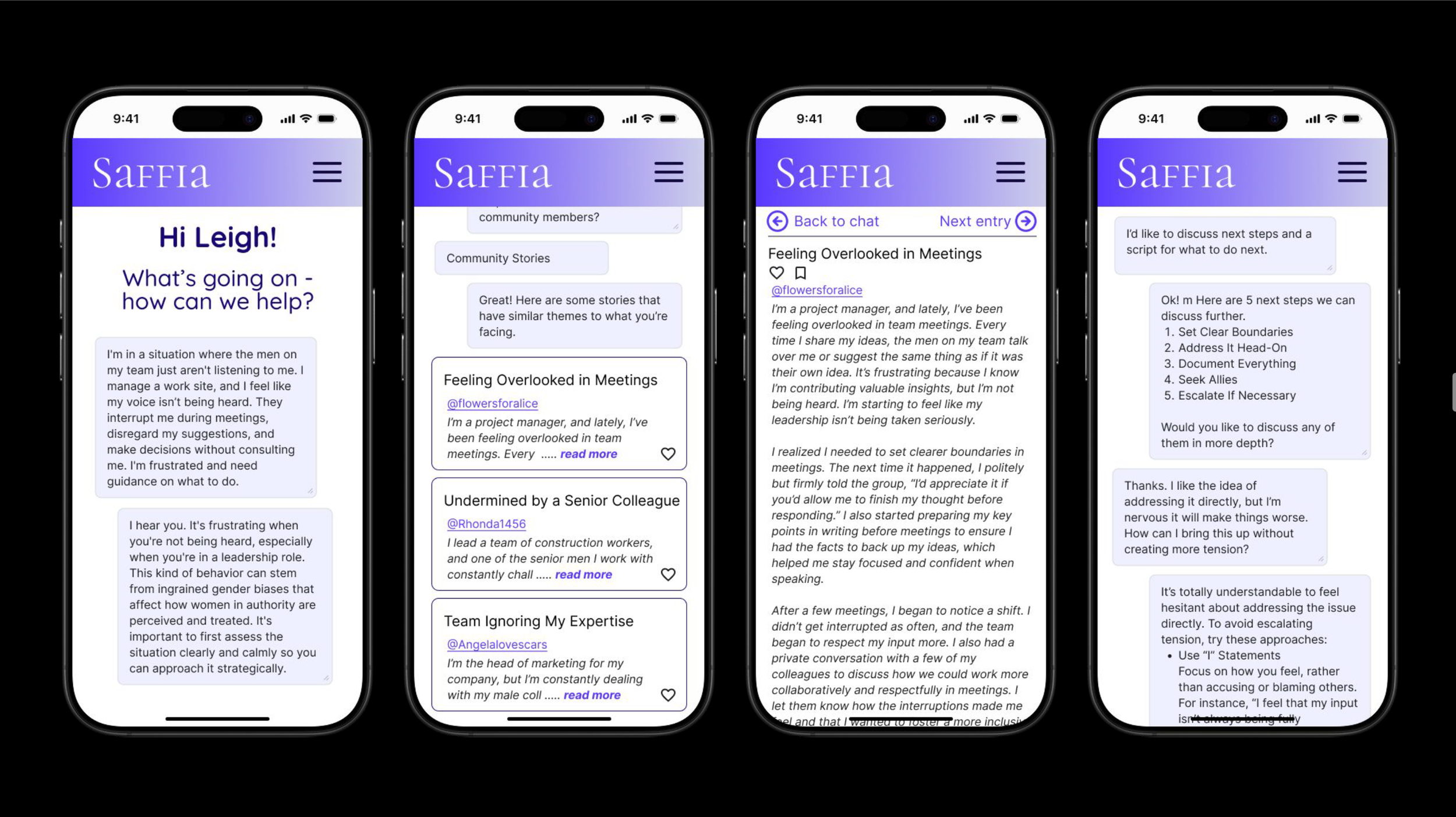

The Solution

An AI-platform and app to combat gender bias that is trained by women, and offers on-demand personalized resources, community advice and insights, and supportive help in the moment someone needs it. The app includes a conversational AI agent to help unpack what might be happening and find patterns in their experience. Users can also create a log of conversations and experiences for reporting purposes and reach out to other platform members whose stories have similar themes. The app would also provide research, legal resources down to the local level, and educational content.

Why an AI-driven Solution?

Incorporating AI into products is huge—and for good reason. It’s new, it’s exciting, and it is going to play a huge role in how we interact with the world long into the future. However, AI is not the right solution to every problem. There needs to be a strong justification for why AI is the right solution for this problem, and an understanding for how your audience wants to interact with AI as well as their level of trust.

AI is the right solution for our product because we want to develop a large repository of information where the most relevant information can be easily surfaced as needed. As communication is a large part of the problem space, a conversational experience felt right and fit how the user would want to use it “in the moment.” Our product needed to help our users recognize patterns of behavior and offer solutions, and pattern recognition is the core of LLMs, making it the right solution for this problem.

However, trust was a large concern for our audience. Many of our survey respondents expressed concerns with societal bias built into LLMs and thought it would not be able to understand the nuance of complex workplace situations. Training the AI with the voices of women’s lived experience and writings is important to building that trust. Not only that, it was important to keep humans at the center of the platform and allow users to also connect with each other and access real stories selected, but not interpreted, by the AI.

To learn about our process and how we arrived at this solution, please continue below.

Understanding and Defining the Problem

With such a broad topic, we needed to understand how misogyny is defined and peoples’ experiences with it so we could narrow the problem space to where we could make an impact. We conducted a dozen interviews with peers, academics, authors, and HR and coaching professionals, collected data from three different surveys at different stages of the project with a total of 234 responses, and pulled information from articles, existing research studies, and other secondary sources.

From our data, we were able to identify three themes around people’s experiences with misogyny: contextualizing it, identifying it, and combating it. Below are some of the insights from our research.

CONTEXTUALIZING

Many women head into the workforce unprepared

Most feel the problem is getting worse

There is a need to understand the history of feminism

Social media, politics, and entertainment are where it is most prevalent

IDENTIFYING

People need help identifying (internally and externally) whether something is misogyny

Consciousness-building (there is less happening in younger generations than previously)

Pattern recognition takes time, so older women have had time to build it up

Many women identify allies who have helped them

COMBATING

How to talk to children about it

Building community and empathy

Finding the right language to foster understanding

There is a want to have shared stories of past issues

Solutions will need to meet the needs of different generations

When we initially began the project, we assumed that dealing with external issues, such as what to say in certain situations, would be the focus. But our initial survey (75% female identifying) found that help with internal self-reflection was what more of our participants were interested in. The responses to this question gave us a clearer path for developing something that people would want to use.

“First I would look at misogyny and am I misogynistic? Start there—and then expand to my inner circle, family members, friends, and be there for them or educating the men in my life.”

Our initial survey (72 participants) found that while external sources such as entertainment, politics, and social media were the primary places participants reported experiencing misogyny, the workplace was highest when it came to face-to-face individual interactions. We decided to narrow the scope of the project to interactions in the workplace.

Leveraging AI to Develop User Personas

We had experimented with incorporating AI tools into our creative process throughout the MA/MBA program. Being able to rapidly iterate and visualize ideas with tools like Adobe Firefly gave us some good results (as well as some bad and outright strange ones.) As this was our final project, it was important to us to experiment with something we had not tried yet, which was building and testing with synthetic personas.

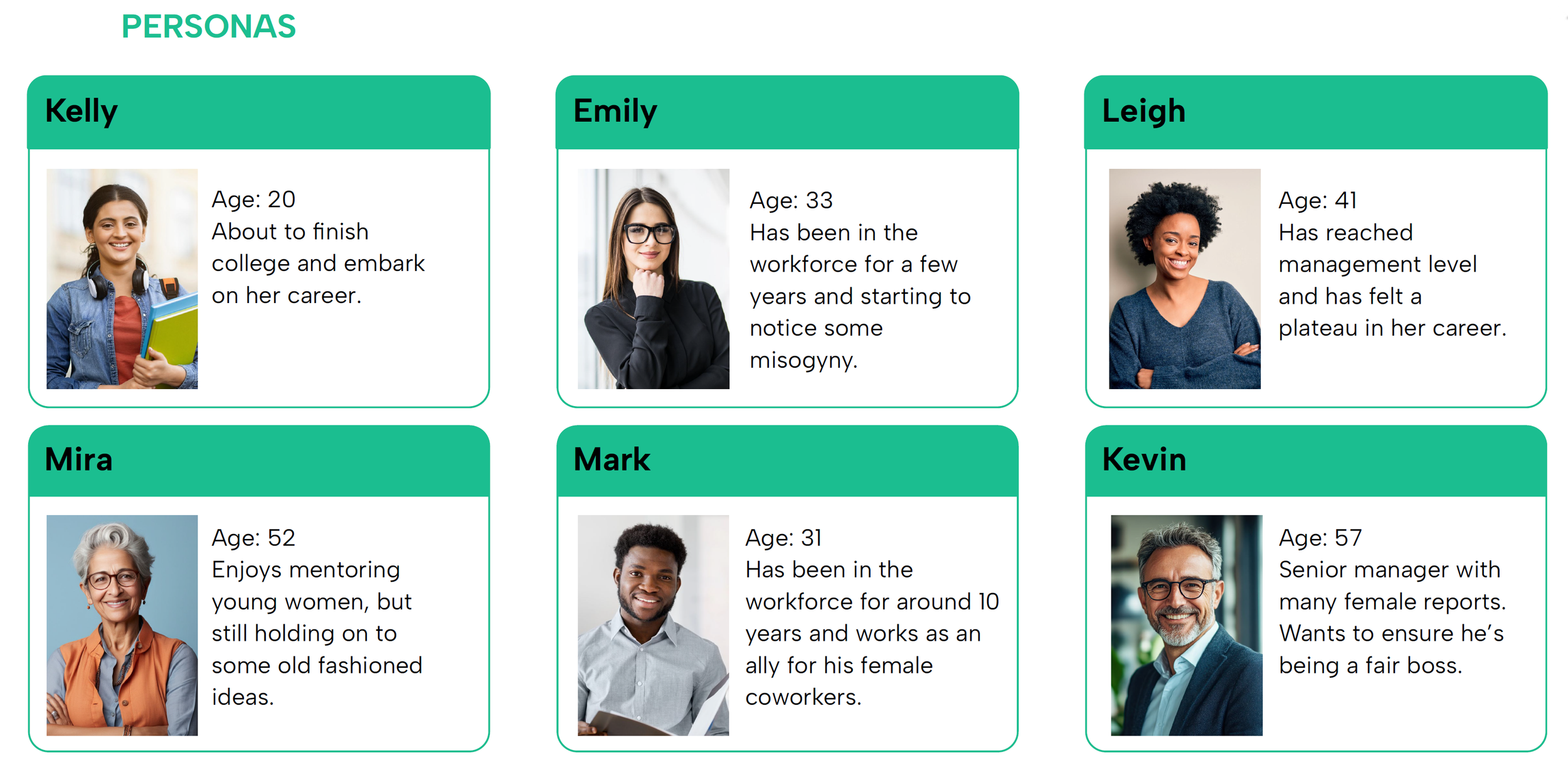

Our six personas

Coming out of our research phase, we developed six different personas with women of different generations currently in the workforce, as well as their male colleagues. We gave them only very basic biographical information to start.

Using real user data to develop personas

By this point, we had now conducted three surveys. The first two ran simultaneously to understand participants’ knowledge, needs, and experiences related to feminism and misogyny. The third focused on workplace experiences, language (which terms encourage or discourage discussion), and which product concepts resonated most. All the surveys were anonymous and included demographic questions. The results were filtered by gender and age to match each persona and then given to ChatGPT, along with the basic biographical details, to generate the persona.

This is one example of an AI-generated description for our youngest persona:

Persona: Emily (First-Person Narrative)

I’m Emily — I’m 20, about to graduate college, and both excited and nervous about starting my career. I’ve worked hard, I care about doing good work, and I want to make a difference wherever I land. But honestly, I already see how gender shapes things — even in small ways.

At my internships, I’ve seen guys get praised for things women said first, or watched women take on the organizing and emotional labor while the credit goes elsewhere. It’s not always dramatic — sometimes it’s just subtle — but it sticks with you.

I don’t want to overthink everything or walk into a workplace defensive. I just want to understand what’s really happening so I can deal with it in a way that feels smart and grounded. I want to feel like I have language and tools to use if something feels off — not just awkward silence or self-doubt.

What I believe most is that people mean well, but culture runs deep. Equality shouldn’t be something you have to fight for — it should be part of how we work together. Still, I know that sometimes it’s up to women like me to name things others don’t see yet.

I want to be respected without having to prove my worth twice. I want to speak up without being labeled as “too much.” And I want to learn how to do that in ways that feel professional and real.

What helps me most is hearing stories from others — women a few years ahead of me who’ve learned how to navigate this stuff, or men who realized how they could be better allies. It reminds me that I’m not alone and that change is possible.

If I had a resource to turn to, I’d want something that gives me clarity and confidence:

Something that helps me tell the difference between normal challenges and actual bias.

A place to learn what I can say or do in the moment.

And a community that keeps me hopeful — that says, “Yeah, it’s hard sometimes, but here’s how we move forward together.”

That’s what I’m looking for — not just answers, but understanding, connection, and courage.

As we iterated our concept and what features our product should have, we solicited feedback from both real-life users and the AI personas. We focused our changes on areas of overlap between the AI personas and the user feedback, and there was actually quite a bit.

What we learned about synthetic personas

As with any AI-driven creative work, the quality of the output depends on the clarity and depth of your prompt. Feeding in filtered survey data helped shape distinct personalities for each user group. Still, it was hard to tell how much of the result came from our data versus ChatGPT’s own assumptions about that demographic. At first, I doubted these personas would add real value, especially since our users were already wary of bias being amplified by AI.

What surprised me was how closely their feedback echoed that of our real users. This unexpected alignment suggested the personas could play a role in shaping our early concepts. Still, I found their responses tended to be overly positive and occasionally slipped into stereotypes when giving examples. The exercise reinforced a core principle for me: while AI-generated personas are useful for fast iteration and initial brainstorming, there’s no substitute for real user insight. Ultimately, genuine feedback from actual people remains essential to refine any meaningful product.

Prototype Development and User Testing

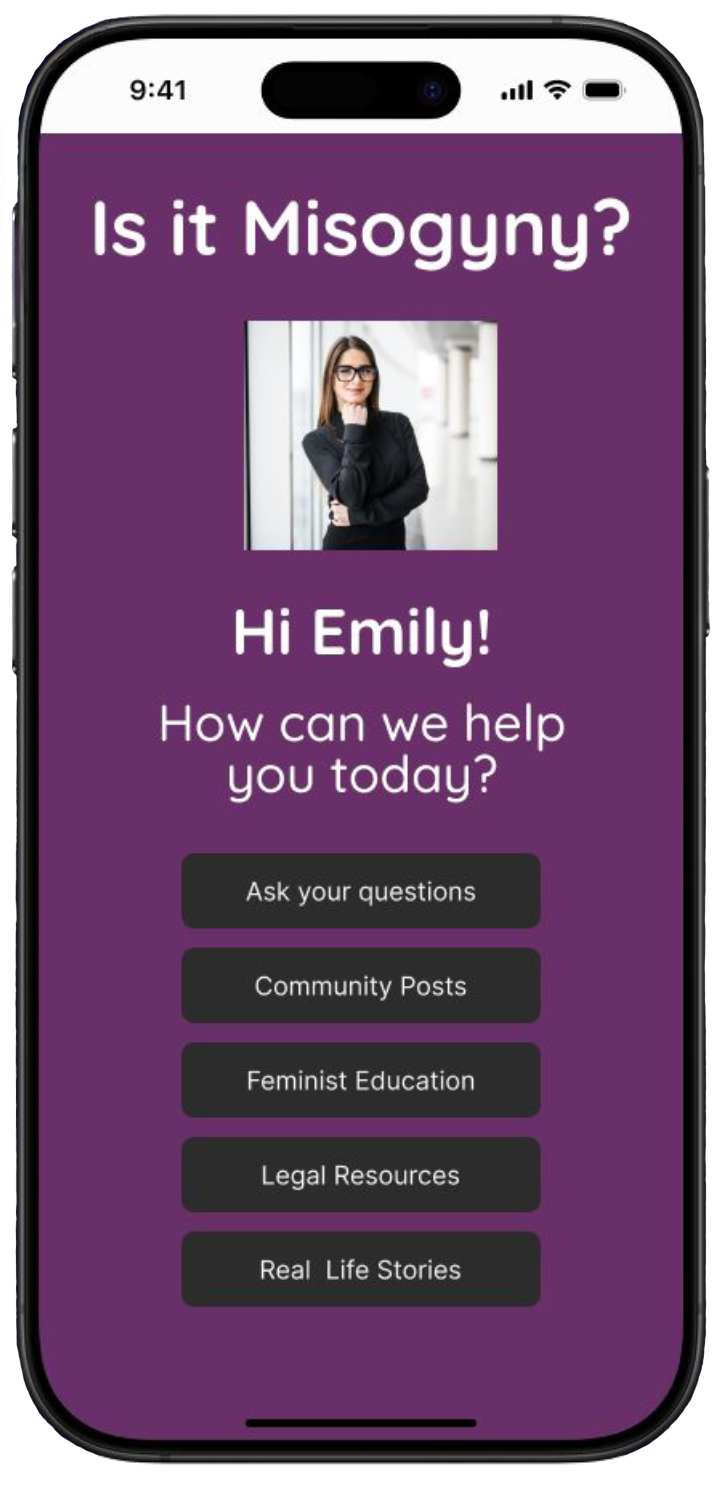

Our initial concept was a multi-faceted website and app designed to help people recognize instances misogyny in their daily lives and provide practical tools to address them. The first prototype focused on the app’s home page and the core features we had envisioned thus far. It used the working title “Is it Misogyny?”, which we moved away from in subsequent iterations.

Initial features:

Chatbot to answer questions

Interactive flow with prompts based on input from users, integrating real-life stories

Community input to drive conversations

Resources for legal rights / quick emergency numbers

Articles / historical pieces available

Interactive feminist education

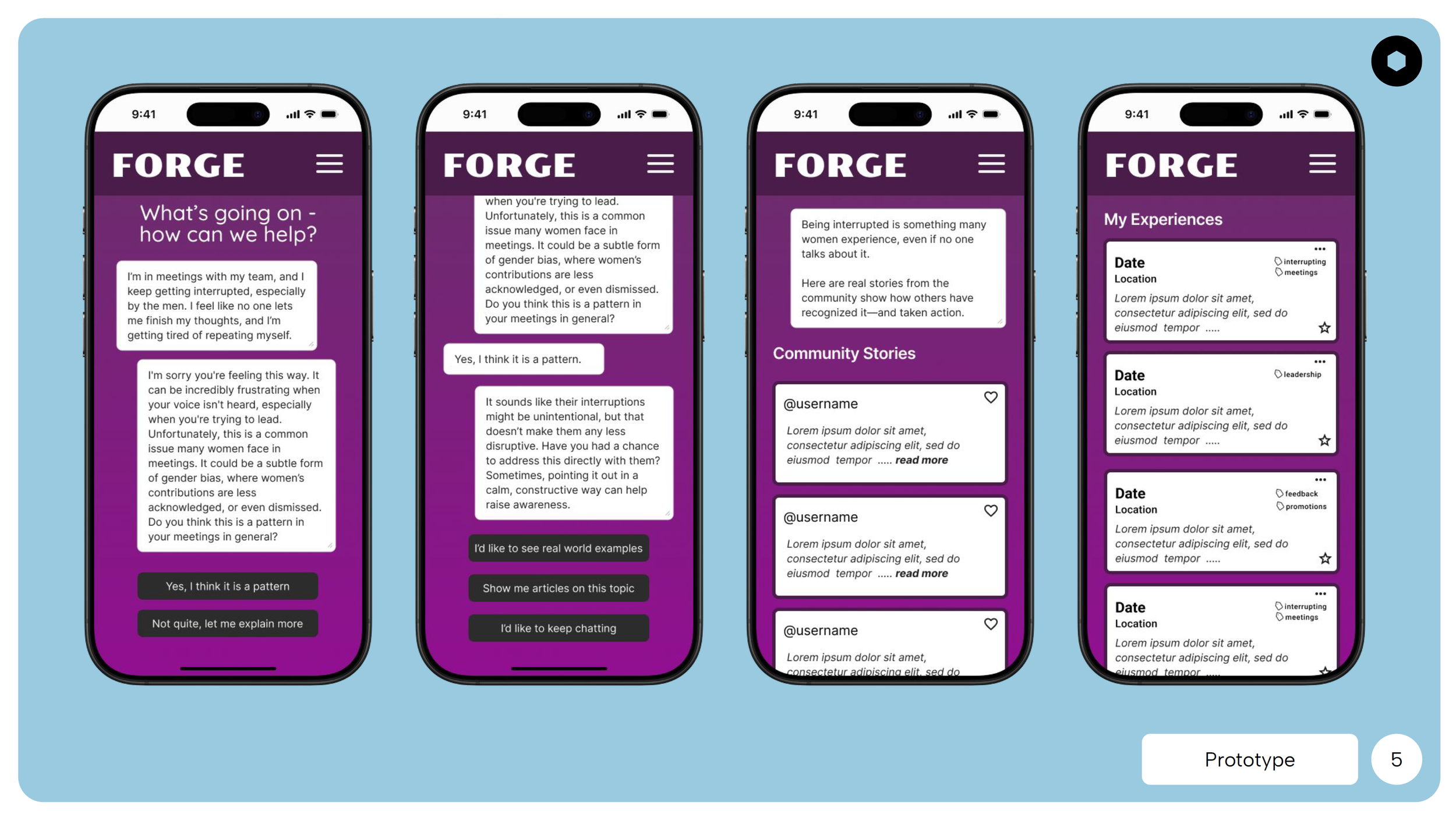

Overall, we received encouraging feedback on the initial concept. Testers found the experience helpful for thinking through responses to challenging situations. Both our real testers and synthetic personas requested more concrete examples of how to respond and suggested adding a private log feature for tracking incidents, which is useful for reporting and self-reflection.

Human testers especially emphasized the importance of community and a platform for sharing stories. Users expressed a strong desire to connect, learn from each other, and build solidarity through shared experience.

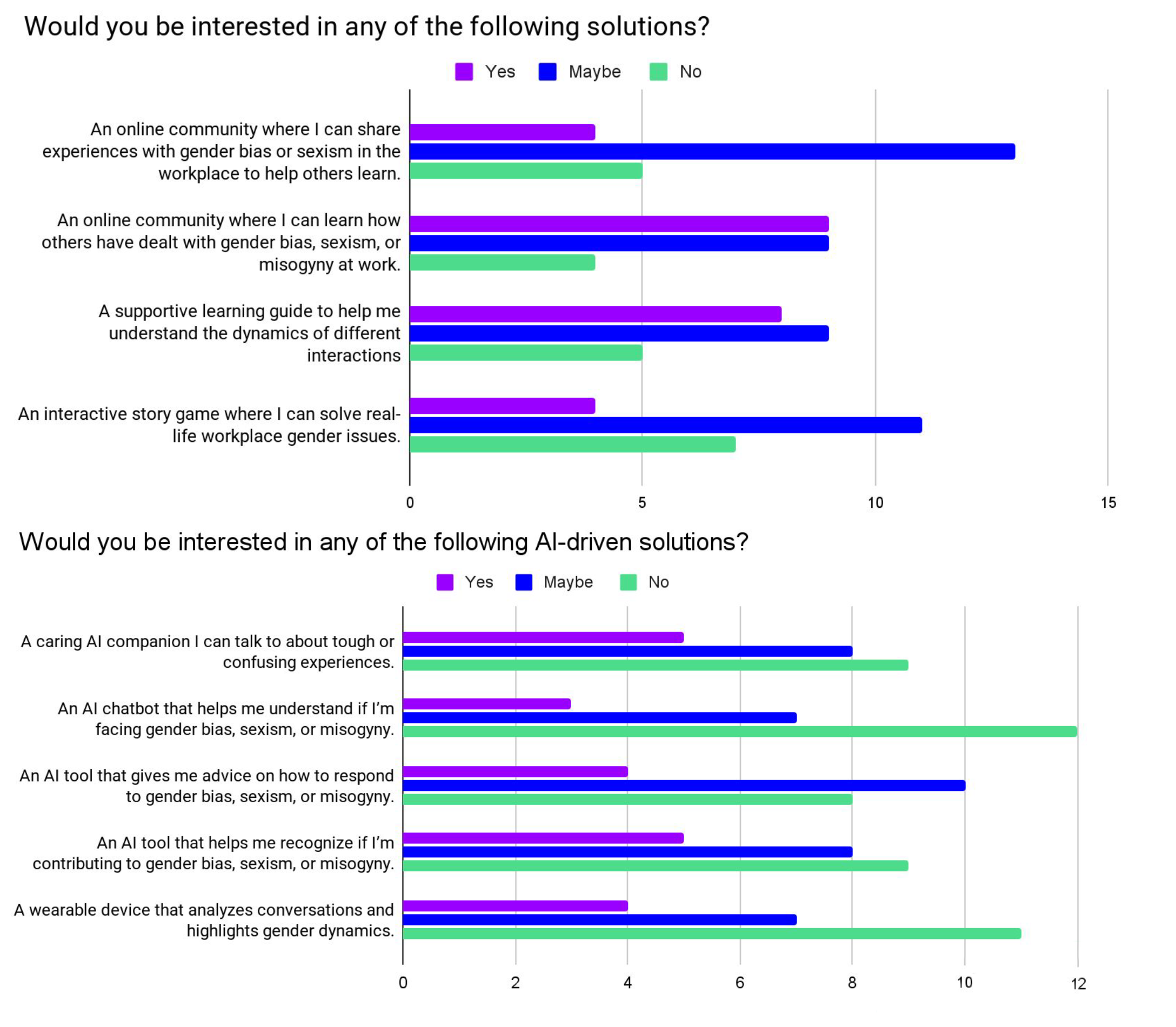

This emphasis on community, as well as caution toward AI, also emerged in our third survey, which tested concept desirability. Many participants wrote in concerns about systemic bias in AI, highlighting hesitancy around technology-driven solutions and reaffirming the value of authentic, human connection in the platform’s design.

From there, we set out to map a new user flow. We still believed that an AI chat feature was essential for providing “in the moment” advice and spotting patterns. The challenge was to figure out how this could work within a community-driven platform and, just as importantly, what it would take for users to trust it. We needed to consider both individual and collective experiences—how a single user might interact with the tool, and how it would function across the community. Incorporating educational resources, relevant legal information, and features for HR reporting also became key priorities.

Initial sketches

First working Figma prototype

Refined prototype and visual design

Building a new “collective wisdom”

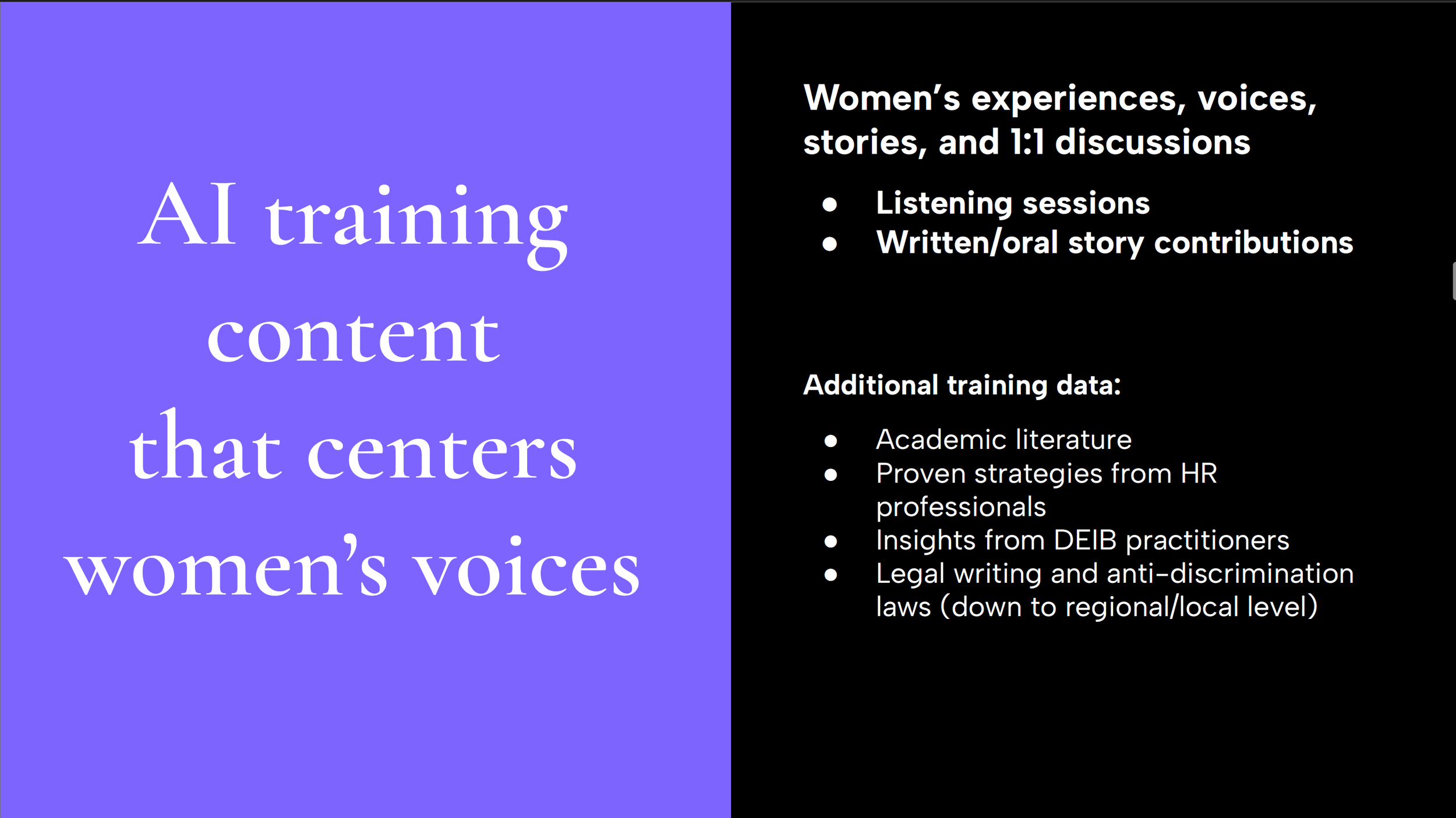

Our audience expressed as much eagerness to help others learn as they had to learn themselves. This motivated us to center our approach on a large language model (LLM) trained specifically on community stories with a women-focused lens. To build this foundation, we planned “listening sessions” where women could share experiences one-on-one or in groups. These narratives would serve as the core training data for the model. Afterwards, users could choose to continue sharing stories that would both educate the AI over time and remain accessible to other users in written form.

While the lived experiences would be the heart of the training data, we would also include a range of established expertise to create a more complete collective wisdom. These sources would include:

Academic literature

Proven strategies from HR professionals

Insights from DEIB practitioners

Legal writings and anti-discrimination laws (down to regional/local level)

Together, the model would provide users with guidance and feedback that is grounded in lived experience while informed by professional knowledge. This ensures credibility and builds trust with our users. Along with personalized guidance, the AI would also connect users to directly to relevant experiences within the community. This approach allows users to benefit from AI insights, contribute to its collective knowledge, and have the option to engage directly with other members. Users can choose to engage individually or as part of the larger community.

From ‘What if?’ to What’s Next

This project started from a broad topic with the goal to design a solution for social good. No brief. No client. Just an ambiguous goal, entrepreneurial mindset, and blue-sky thinking. Coming from a project-driven agency background, this was a refreshing opportunity to fully let research and the question “what if?” steer our ideas to create something new. It can be intimidating to stare at a broad, ambiguous, and complex issue and wonder where to even begin. I find that ambiguity exciting because that is where you start uncovering the story and piecing the information together. It’s the part of the process where anything is possible. A project like this could go in many different branching directions, and it can be difficult to know which branch to prune and which to let flourish. We knew we had picked the best path for our project when we would informally pitch the idea to other colleagues, students, and design leaders throughout the semester and got genuine excitement in return.

For now, the project remains a concept and a possibility. There is much more research to be done and questions to think through. If we were to bring this concept to life, we would need to develop partnerships, secure funding, and build a team. We would also need to collect a significant amount of data. We developed a rough roadmap for what that would look like.

Though the project is not in active development, this roadmap shows how Lindsey and I envision turning the concept into a full-fledged product.

I want to give a huge thank you to our project mentor, Susan Major, Founder and Principal Consultant at Ilya Labs and Postdoctoral Fellow in Entrepreneaurship at West Virginia University. Throughout the project, she challenged our thinking, pushed our ideas, and continually inspired us. Thank you, Susan!